Why has your LinkedIn feed gotten so terrible?

There are actually a few reasons, but I’d like to make the case that it stems from a breakdown in understanding of what type of product LinkedIn is.

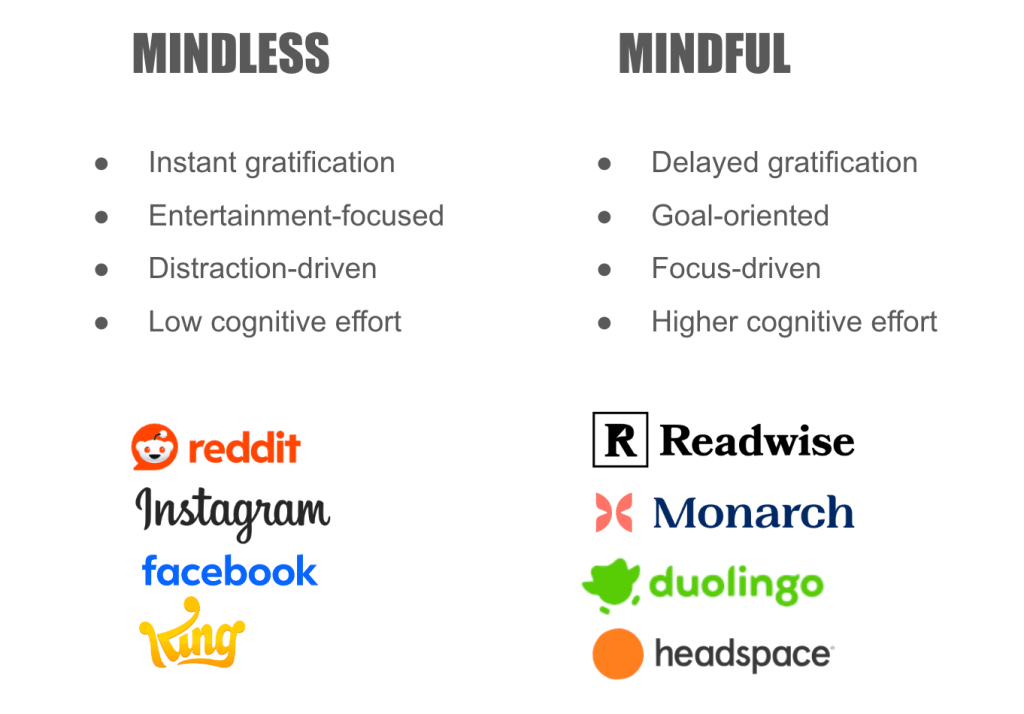

Let’s break down modern software applications into two very broad categories:

Mindful products: These are goal-oriented products. They generally require more user investment. The main goal is either some longer-term benefit (e.g., mental, physical, financial health) or a short-term productivity-oriented benefit. Examples include meditation apps like Headspace, fitness trackers like Fitbit, personal finance tools like Monarch, and learning tools like Duolingo or Quizlet.

Mindless products: These apps are more about entertainment and fun. The main benefit is in the moment. Games, streaming apps, and social media broadly fit into this bucket. They help users take their minds off things, get entertained, or otherwise pass the time.

These two categories of products have fundamentally different dynamics. To use mindful products, users typically have to turn their brains on. When using mindless products, users turn their brains off—and this is by design. In other words, mindful products tend to tap into our System 2 brain circuitry, while mindless ones rely on System 1. My argument in this post is that many problems with modern software stem from misapplying product patterns that work for mindless products to mindful ones.

So Why is it Bad if You Apply Mindless Patterns to a Mindful Product?

It ultimately comes down to two pieces: short-termism and brand damage. Mindless products often focus on short-term engagement metrics like daily active users or session length. This can detract from the long-term benefits that mindful products are meant to provide, such as sustained mental health improvements or skill development.

Using mindless patterns in mindful products can also result in brand damage. Users come to mindful products with an expectation of value and respect for their time. When these products employ mindless tactics, it can lead to a loss of trust and damage to the brand’s reputation. Users may feel manipulated, leading to negative reviews and decreased loyalty.

This isn’t to say that all applications of mindless product patterns to mindful products are bad. Take Duolingo, for instance. While it’s fundamentally a mindful product designed to help users learn a new language—a goal-oriented, long-term endeavor—it successfully incorporates elements like streaks, gamification, and rewards. But Duolingo integrates these patterns in a way that reinforces the user’s learning goals rather than detracting from them. Fun and gamification is actually part of the app’s core identity, like the logo (a playful green owl), the primary messaging (“The free, fun, and effective way to learn a language!”), etc. It might sometime feel borderline tacky, but it’s always focused on the user’s goal: learning.

So if you take away one thing from this article, it’s that mindless patterns can be carefully and thoughtfully applied to mindful products only when clearly in-service of a user’s goals. Going back to that LinkedIn example, the reason the product feels like a bit of a mess is because you’re probably going to LinkedIn to connect with people, to hire, to get hired, or to learn. Instead you end up being detracted from that goal by content and engagement tactics that are often so cringe-worthy that they have inspired a whole subreddit.

How Did We End Up Here?

Short-term Metrics are Easier to Move

One reason for the misapplication of mindless patterns is that short-term metrics are easier to track and improve. In an increasingly data-driven industry, metrics like daily active users, session length, and click-through rates are straightforward to measure and can show immediate results, especially under pressure from existing/prospective investors or company leadership. In contrast, the actual benefits of mindful products, such as improved mental health or financial stability, are harder to quantify and take longer to manifest. This can lead product teams to (mindlessly) prioritize short-term gains over long-term value.

Ease/Simplicity

Developing mindful products also requires more thought and effort compared to mindless ones. Mindless products thrive on simplicity and ease of use, often optimizing for the least amount of user effort. Growth hacking and funnel optimization can be used to quickly scale user engagement and retention. In contrast, mindful products demand a more nuanced approach, considering the long-term value and sustained benefits to the user. This often involves more complex development processes, including user research, personalized experiences, and thoughtful design to ensure the product genuinely enhances the user’s life.

The Curse of Authority

A final reason is the influence of early successful mindless products. Games, streaming services, and social media platforms were among the first apps to achieve rapid growth and massive user engagement, attracting significant attention and investment. Product Managers and Growth Marketers from these companies would go on to lead or invest in the next generation of companies, and they would write books like “Hooked” and popularize terms like “growth hacking.” As a result, many product designers and developers looked to these successes as models, even when building more mindful products. This has led to the adoption of engagement tactics that may not align with the long-term goals of mindful products.

How to Build Mindful Products

User-aligned Business Model

The first step is to choose a user-aligned business model. I’ve personally found that a company’s business model is more important than culture, mission, or anything else in shaping a product. Business model warps all incentives around a product.

What business model you choose may differ depending on your product and the value you’re providing for users, but for goal-oriented consumer products, a recurring subscription is often a good place to start. At Monarch, we built a subscription-based product despite many of our (existing) competitors offering their product for free and monetizing through in-product advertisements or by selling data. We found that those competitors’ products essentially turned into top-of-funnel lead generation tools rather than best-in-class consumer products, mostly due to the gravity of their business model.

Similarly, it’s important to choose the right representative metrics. This can be a challenge because, as described above, some metrics might take time to fully materialize, but you can usually start with something simple (like, do users start a subscription for my product) and developing a more complex / predictive model over time (like, does how users use my product predict whether they I will retain them for a long time).

Avoid Disrespectful Design

As you’re working on your product and your funnel, you need to always keep in mind that you’re working on a mindful product, not a mindless one, and avoid disrespectful design. In a mindless world, users are, well, mindless creatures that need to be mechanically pushed through some funnel without thinking too hard about things. Now, even users of mindful products might be busy and impatient, but they’ve come to your product for a reason or goal. So instead of disrespectful design, use patterns that align with and remind users of that reason or goal.

For example, in a mindless world, almost all friction is bad. You improve things by reducing steps and actions a user needs to take. However, in a mindful world, you can start to think about “good friction” and “bad friction.”

I’ve seen many products (including Monarch) where continuing to add steps in an onboarding funnel improves user experience and outcomes. A simple version I ask most product teams to test involves adding a step asking users (via multiple-choice) why they’ve come to your product, as a way to help remind them what their goal is and reinforce their motivation. Bonus points, of course, if you use the information you collect during onboarding to later personalize or improve user experience. But even if you don’t, simply realigning or reinforcing a user’s goals can result in better outcomes. You’ll notice that many popular products like Noom and Blinkist have increased the length of their onboarding funnels with not just one, but multiple similar-in-spirit survey questions.

Mindful Use of Engagement Tactics

Another aspect of respectful design is the careful use of engagement tactics like push notifications and gamification. While these tactics are effective in driving user engagement in mindless products, their overuse can be detrimental to mindful products. Users of mindful products expect value and respect for their time. Excessive notifications can feel intrusive and reduce the perceived value of the product, leading to frustration and disengagement.

This isn’t to say you shouldn’t use these engagement tactics at all. But when used, push notifications and gamification elements should clearly tie back to the user’s goals. For instance, instead of frequent reminders to log in, a mindful product might send notifications that celebrate milestones or offer valuable tips related to the user’s goals. This approach ensures that these tactics enhance the user experience rather than detract from it.

Intent as a Spectrum

You should also view “intent” (how much a user wants your product) as a spectrum. Some users will have high intent for your product (think of the folks camping outside the Apple Store for the latest iPhone), and some users will have low intent (folks who casually stumble across your product). Now, with a mindless product, you can just shove people through your funnel and ignore their level of intent. With mindful products, on the other hand, you want to only let high-intent users through your funnel, or convert low-intent users to high-intent ones before letting them through.

Generally, you want to avoid letting low-intent users through your funnel to avoid funnel corruption. Funnel corruption occurs when you’ve created a situation where users are going through your product (onboarding, using your product, etc.) without having high intent for it or being goal-oriented. Since you’re probably data-driven and looking at and A/B testing your conversion rates, you’ll see behaviors that may not be reflective of what you actually want to achieve. You’re testing the wrong users—you’ve broken your feedback loop.

The easiest way to get high-intent users is to filter for them by having users make bigger commitments earlier (such as requiring payment or significant user input upfront). This approach, while counterintuitive for mindless products, helps in ensuring that only highly motivated users progress through your funnel. This can lead to better user outcomes and a more dedicated user base. And in fact, some of these techniques, like requiring commitment, can increase intent too (via the “commitment effect”).

Alternatively, you can often build up the intent of low-intent users who aren’t ready to make a big commitment by having them make a series of micro-commitments that help them bridge the gap between their mindless and mindful brains. The key, again, is to focus on their end goal (what they’re trying to accomplish) rather than your end goal (which might just be more users and revenue) to avoid force-feeding your funnel.

Conclusion

In summary, understanding the fundamental differences between mindful and mindless products is crucial for creating meaningful and effective software. When products confuse the two, they leave users confused as well. You’re heading to LinkedIn to apply for a job, or stay up-to-date with industry news. But you’re instead bombarded with engagement notifications and a click-bait-driven infinite feed.

I’ll conclude by noting that I’ve tried to discuss mindless / mindful products while withholding judgment about working on either, but ultimately, technology is a tool we can use to help people better themselves, or to take advantage of them. Many conscientious designers and developers find much greater pride and satisfaction in their work when they use patterns that align with users’ goals and values. By focusing on user-aligned business models, thoughtful design, and respectful engagement tactics, we can create products that truly serve the needs and goals of users—and we can feel good doing it. Let’s push ourselves to do work we are proud of, ensuring our creations genuinely enhance users’ lives.

I personally sleep much better at night working on something mindful.

Special thanks to: Phil Carter for feedback and to Subversive (a Slack group he organizes for Founder/CEOs and Product, Marketing, and Growth leaders of consumer subscription businesses to connect, learn from one another, and share best practices) for inspiration to turn a half-formed comment in a Slack thread into this article. Thanks to Kosuke Mori as well for providing feedback and helping challenge (and resolve!) some of my arguments.

Where would dating apps fall? They seem both mindless and mindful in terms of user intent and activities (mostly mindful with a bit of mindless), and mostly mindless as far as business goals/metrics. I think LinkedIn might straddle both categories too, with more of a balance between mindful and mindless. Then there’s enshittification and its role in making products more mindless and focusing on the short-term.

Originally your post caught my attention in my inbox because you started it off by asking a question just like the one in a post I published yesterday about why LinkedIn is so miserable these days.

LikeLike